AUDI A2 VS. BRISTOL 403

1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9- 10- 11- 12- 13- 14- 15- 16- 17- 18- 20 -21 -22

It all began when Anna said that she needed a car to use in Firenze. I gave her one of my beloved Jaguars, a 1992 Jaguar XJ40, and she liked it a lot; but this Big Jag, though elegant and downright classy in her Solent Blue livery, was way too large for Tuscany’s narrow streets and crooked alleys. We needed a smaller car, but, of course, I couldn’t surrender to the purchase of a modern Korean supermini; I hate Smarts with a passion, while small Opels or Peugeots are not my cup of tea, they are too common. It had to be something special, possibly vintage, with real character.

I have admired the A2 since I road-tested it in Cote d’Azur in 2000 for its engineering integrity and overall quality; being only 3,83 meters long, with a very short nose and lots of space inside, it was a perfect choice for Firenze. Of course, I didn’t want to buy Anna one of the ubiquitous, cheap silver or black TDI on sale all over Italy; I wanted an example with some panache, so I looked for an A2 with 1,4 gasoline engine, OSS (Open Sky sunroof) and a not-too-common colour. I found a 2002 A2 in Pine Green ‘Perleffekt’ with sunroof and 1,4 engine, I bought it and I restored this amazing little car in some weeks’ time (admittedly, at the end it cost almost as much as an A8…) and now it lives in Anna’s garage, in Firenze, where she uses it for the occasional daily commuting.

Driving the A2 again was a revelation. I found it to be compact and extremely agile, fun to drive and with an extremely high quality all over; it hasn’t aged a bit since 2000. I liked it so much that I decided to buy another one to use in Bologna, as an alternative to the all-electric Citroen C-Zero I am also driving, delightful as a city runabout but plagued with a ridiculously short range. So I found in Brescia at a fairly good price another A2, a one-owner example with gasoline engine, Open Sky Sunroof, in ‘Kristallblau Metallik’, and bought that one for me.

Now that I have bought a second Audi A2, all my friends (my wife too), wonder what I find so amazing in this unusual little car. Well, probably some of this fascination comes from the fact that it shows some very interesting affinities with my beloved Bristols. You may think that I am talking nonsense, or at least that I’m straining quite a lot a connection that may sound quite tenuous when I say that these two apparently opposite cars are intellectually quite similar. Therefore, let me point at some details that show why, if a car enthusiast like myself appreciates Bristols, he may also be insanely attracted by Audi A2s as well.

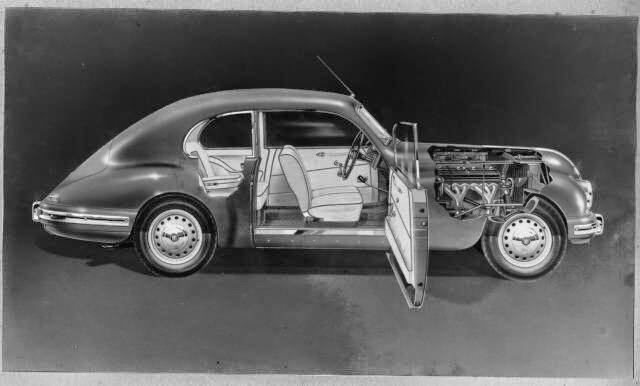

To begin with, one word: aluminium. The liberal use of this light metal and of its sophisticated alloys was one of the most striking features of the Bristol 401 when it appeared, in 1949, and it was equally noble and interesting four years later, when the 403 was introduced. Its aluminium body was both refined and technically advantageous, as it allowed the panel beaters of Bristol to work on those shapes without having to provide the tooling for more expensive steel panels, adjusting the thickness of the panels according to its structural needs.

Of course, steel panels would have been required for a mass production car, but the Bristol ‘Aerodynes’ (as the 401 and 403 are known to connoisseurs) were never intended to be mass-produced motor cars, on the contrary they were sophisticated, very expensive and extremely well refined cars for an élite of wealthy connoisseur. Their engine was not very powerful, because its displacement was comparatively small; it was a sophisticated straight-six engine with pushrod distribution and overhead valves, that had been predated from the excellent pre-war BMW with most of its suspension and drivetrain. The interior of those Bristols was classy, extremely comfortable and magnificently appointed, with plenty of space, an incredibly complete instrumentation and all the comforts and luxuries that one would expect from a car that, at the time, was one of the most expensive for sale in England and surely the most technically advanced.

That straight-six was very good for its displacement, but there were rivals who could easily outperform the sophisticated Bristol with the sheer brute force of their much larger engines, for example Jaguar with its beautiful straight-six XK engine. Less noble than a Bristol, maybe, surely more powerful, giving the XK120 a higher overall performance. It was also a fascinating object to look at, but the engine was not the first thing that one would admire in the Jaguar. The XK120 was incredibly beautiful; whilst the styling of the Bristol, though it had been derived from some outstanding pre-war designs of the fabled Carrozzeria Touring in Milan, has been widely criticised for being less than harmonious and surely not to everybody's liking. The Bristol was, in many ways, an engineers’ car, one could say an aeronautical engineers’ car; aerodynamic efficiency was the main target, and everything else be damned.

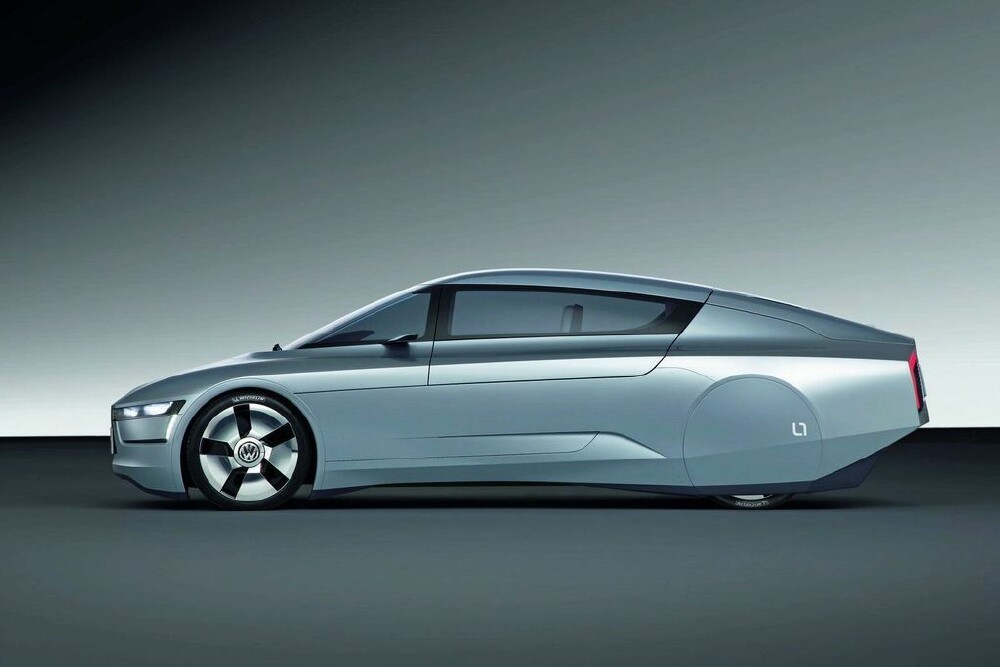

So far, we have taken a look at the Bristol ‘Aerodynes’, so let's examine now the A2. The A2’s mastermind was none less than Ferdinand Piëch, whose aim to make his cars lighter and more efficient is legendary since his days as head of the Porsche Rennsport, where he conceived featherweight cars like the hillclimb-winning ‘909’. He wanted a car that could go from Stuttgart to Milan carrying four people and their luggage on one single tank of fuel, and not a big tank at that. (Bristol too insisted on the long-range ability of its 401/403 of carrying four adults and their luggage on long-range trips, effortlessly). Piëch’s brief included the notion that the A2 had to be ‘a small Audi’, emphatically NOT ‘a cheap Audi’. Exactly like Bristol insisted on not diluting the airplane firm’s engineering excellence in the car project.

The A2 was designed to put to good use the huge expertise that Audi was amassing in cooperation with Alcoa in the use of aluminium in the manufacturing of large, very expensive saloons like its flagship, in some way exactly the same process that brought Bristol to transfer to its production cars their experience on aluminium developed for the production of combat airplanes like the Blenheim or Beaufighter. The result was that Audi could flaunt a kerb weight of only 895 kgs for its sophisticated supermini, an incredible result when compared to the direct rivals of the same class, and the weight reduction was so important in the ‘8Z’ project that the options list reported also the weight of each accessory, so every customer could calculate the impact of his order on the final weight of his A2. The direct rival, the first series (‘W168’) Mercedes-Benz ‘A-Klasse’, weighed 1.020 kgs in its base form. The Bristol 403 sported a weight of 1.225 kgs, decidedly low for its class, that compared favourably with the 1.422 kgs of the Jaguar XK140 coupé, and one must also remember that the latter could seat only 2 adults; if you wanted a full four-seater from the Coventry firm you had to buy a MkVII Saloon, whose interior space would compare better to the 403’s but weighed no less than 1.753 kgs.

The A2’s styling has been controversial from the beginning, partly because, exactly like Bristol's, it was a classic example of form following function. Luc Donkerwolke styled an innovative design that was aerodynamically very efficient, but, having to operate in an urban ambience, had to be very compact and compromises had therefore to be made to combine interior space, external compactness and aerodynamic efficiency. It was a superb package, probably the last of the Bauhaus-influenced cars ever, but its styling was not liked by everybody and somebody even consider it just plain ugly, a consideration that undoubtedly rings some bells around Filton.

The unconventional styling of both cars was a direct effect of the obsessive search of their designers for a better aerodynamic efficiency. Although they are as much different from each other as two cars can be, the 403 and the A2 show a very similar, class-beating Cx of 0,25, thus it is not surprising that the top speeds are very similar, respectively 104 and 107 mph whilst the time from nought to 62 mph is in both cases a comparatively sedate time, the lightness of the Audi allowing the little German to sprint to that speed in 11,3 seconds, the 403 reaching the same speed in 13,4 seconds. Mind you, 104 mph and 0-62 mph in 13,4 seconds were impressive results for a 2-litre car in 1953!

There’s more. Speaking of peculiarities, both the Bristol and the Audi offer an external lock only on the driver’s door and you open the flap protecting the fuel filler cap pressing a button located on the LH side door pillar in both cars. The Aerodynes have a freewheel on 1st gear to ease the driving at slow speed in traffic, and the same solution is used on the super-thrifty ‘3L’ A2. All the A2s, however, have a freewheel system…on the alternator, to reduce friction and therefore fuel consumption when its work is not necessary.

Whilst Audi was developing this sophisticated aluminium body, using all the more advanced technologies available to make it both light, rigid and space efficient, the A2s engine was shared with some less glamorous models of the Volkswagen Empire, namely the 1.4 litres used on the little Volkswagen runabouts. The gasoline engine was therefore a carryover, exactly as on the Bristol, whose pushrod engine was ‘borrowed’ from the racing pre-war BMWs, but again it still is a comparatively high-performance one with a highly sophisticated design, as the Audi’s is a straight-four with twin overhead camshaft and four valves per cylinder.

It is quite interesting to see that the specific power of the two engines are quite similar, though there are almost 50 years between the production of the two units; the 2-litres ‘100B’ engine of my Bristol 403 produces 100 hp, therefore 50 hp per litre, while the 1.4 litres ‘BBY’ unit of my 2005 A2 produces 75 hp, with a specific power output that is only a little teensy bit higher (53,5 cv/litre) than the older British unit.

The aluminium widely used underbody of both cars (and, in the Audi, also into its chassis) was regarded as a sophisticated detail and a very attractive feature when the buyers of a new A2 or 403, wealthy enough to afford to buy such an expensive vehicle, could also happily pay for any repair; those costs became increasingly worrying for the subsequent owners of second-hand cars, who became very worried about potential costs of repairing such sophisticated panelling.

At this point one must remember that both cars were at the time of the introduction extremely expensive, at the top of the price lists of their market segment respectively in 1953 and in 2000. The Audi A2, exactly like the 403, was meant to be the perfect car for someone wanted the most and was prepared to pay for it, as in an A2 you find exactly the same level of equipment and the same overall quality of the larger Audi saloons and station wagons, the same switches, upholstery, equipment, and an enormous list of optional that an owner could specify, of course at a very high cost but with the absolute certainty of obtaining the highest quality in every part of this little car. Exactly like a Bristol customer could trust the Filton firm to deliver him a perfectly appointed car in 1953, provided that he was ready to fork out the hefty sum required for the delivery. If the A2 was a new Millennium architects’ car, so the Bristol must have been a sophisticated choice for a modern, technically oriented and very individualistic businessman of the early Fifties.

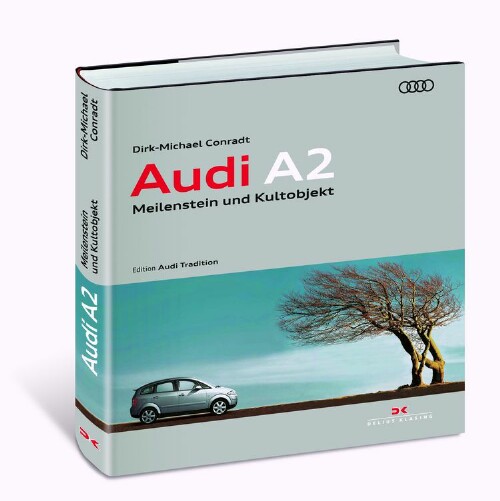

One can rejoice in the absolute scarcity of books and Web sites devoted to those 2 eccentric automobiles, seeing in this a proof of their exclusivity, and in the high quality altogether of those few books. ‘A2: Meilenstein und Kultobject’ by renowned Porsche historian Dirk-Michael Conradt and ‘A Private Car’ by no less than Leonard John Kensell Setright are two monumental tributes to the uniqueness of their subject and a must-have for any enthusiast of great books and good writing (especially LJKS’).

Both cars have been largely in your ignored by the Great Unwashed. Making a direct comparison of their commercial success vs. their direct rivals, one sees that the 401/403 reached a grand total of 898 saloons built plus maybe 12 ‘402’ convertibles against the 12.055, of which 2.672 were fixed-head coupes, of the Jaguar XK series; whilst Audi found only 176.377 buyers for its sophisticated aluminium jewel, Mercedes-Benz sold more than 1,1 million units of their original W168 ‘A-Klasse’, elk test and all. Maybe this was not so bad for Audi, as every A2 was allegedly built at a loss of Euro 4,000 per car, piling up a loss of more than 1 million Euros before Bernd Pischetsrieder killed it in 2005 (allegedly as part of an internal battle between him and Piëch.)

A few years after they went out of production, both the Bristol and the Audi reached a bottom level of valuations that made them extremely affordable for everybody, even if not many were so eager to buy one of those complex cars and tackle an unavoidably expensive restoration (I speak for a direct experience in both cases), so they are slowly becoming a rara avis.

On the other side are the devotees of both marks and of both models, that simply think that no other car may fit their needs as well as an old 1953 Bristol 403 and a much more modern, but already classic, Audi A2. In my garage, there’s space for both of them.

A great book written by Dirk-Michael Conradt and published by

https://www.delius-klasing.de/

Every A2 owner must have one...